The following is an opinion piece based off personal research about the complexities of internet addiction and what it means for internet users moving forward.

In this article I will cover:

The origins of internet addictions

Where internet addiction stands today

Algorithms and technological advancements

Human efforts to aid in tech overuse

Who’s responsibility is it to change?

Closing notes

It’s the 90’s and using your computer is a practice in patience but a well-rewarded one. The web is a novel and enthralling creation and hundreds of new sites are being produced daily. Choose to browse Yahoo, email your fav celeb, or auction your heirlooms. Unsurprisingly so, it wasn’t long after the World Wide Web became popularized that the term “internet addiction” was coined. Kimberly Young was one of the first psychologists to pioneer data in the field of internet addiction and published her book on the subject, Caught in The Net, in 1998.

A phone call with a friend triggered her curiosity about the phenomenon in which friend revealed she was filing her husband for divorce due to his chronic internet use. His obsession led to unaffordable phone bills and he abruptly became physically and emotionally removed. Upon hearing this, Young began to study a completely new area of addiction – one relating to machines. She conducted a survey questioning users about their internet behaviour and 496 people, primarily female, responded. This assessment would become the first of its kind to understand excessive internet usage and was named the Internet Addiction Test (IAT). She reported that 80% of individuals surveyed could be classified as internet addicts.

The sources who spoke of their technical malaise experienced the rush of online attention far before Myspace was created. For example, take 34-year-old Jeanne, a homemaker with two toddlers, who discovered the enchantment of online chat rooms. Here she found women with similar lifestyles and interests as her. She experienced fresh feelings of self-confidence, saying she felt more “attractive and interesting” and that nothing else made her feel this way. Jeanne especially enjoyed how she could maintain an unkempt appearance and still connect with her friends without feeling scrutinized. Unfortunately, all the glory began to dim when her once-a-day check-ins became an all-consuming practice, and her marriage and home began to fall apart. Young stated another respondent became so attached to an online friend that when they stopped communicating, the respondent cried for days.

An alternative internet user expressed his affinity to the expansiveness of the web, saying he received a rush every time he connects to the “intensely powerful information whirlpool.”

Young introduces Avant Gard terms for the time such as Mindthrill and Terminal Time Warp to express these cyber experiences. She describes Mindthrill as the phenomenon of intense stimulation when interacting with the webs interminable content selection. While Terminal Time Warp a vintage term for Doom Scroll, signifies the time that passes unknowingly and quickly online.

Though Young’s work is crucial, for today’s time it could be considered a little vintage. The world of chatrooms, gaming, and online shopping has evolved ten-fold and phrases such as remote jobs, e-learning and artificial intelligence are colloquial now. Internet use is ubiquitous and spending your day as a recluse in your room online, doesn’t necessarily mean your addicted anymore.

Defining the undefinable

Internet addiction isn’t classified as a disorder in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) however Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) is listed as a “condition for further study,” and the WHO recognizes IGD as a diagnosable disease. But it’s not that it’s not seen as a problem; with how multifarious the internet is, it’s difficult to pinpoint what the problem is to begin with. Is it social media, video consumption, information overload, pornography, online shopping, gambling? Not to mention a lot of media is consumed all at once now with Netflix flashing on your computer screen, Instagram refreshing on your phone, and a notification darting around to remind you to feed your virtual pet bird.

The ambiguity of the issue has called into creation terms such as internet dependency, problematic internet use, compulsive internet use and pathological internet use as synonyms for internet addiction.

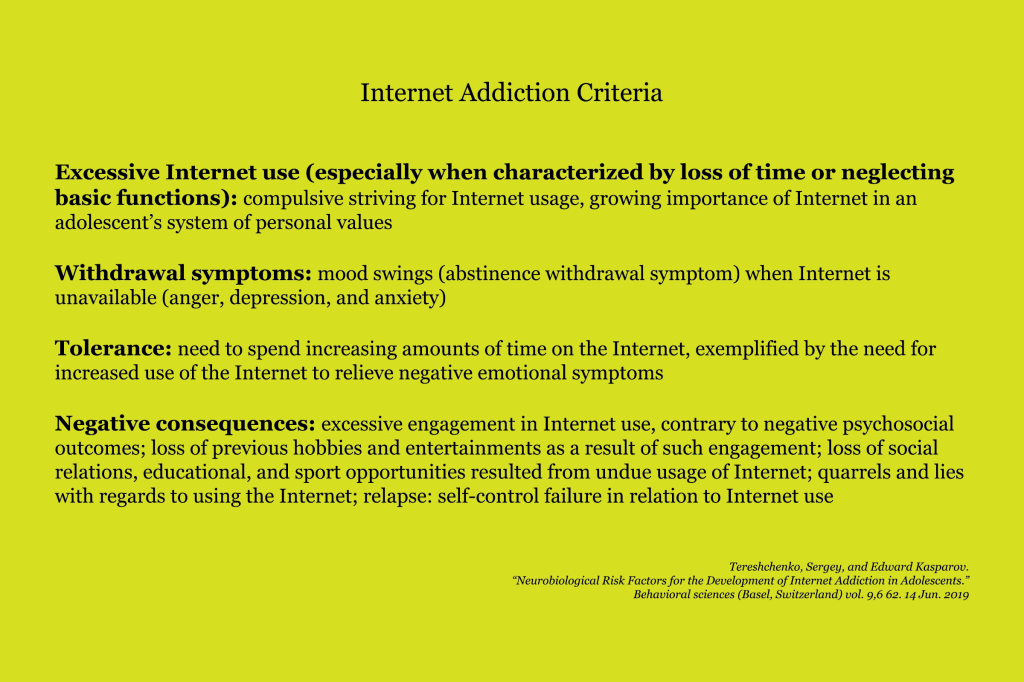

It’s been agreed upon through conceded research that symptoms include neglecting basic self-care, losing track of time, experiencing withdrawal signs, requiring increasing amount of usage to satisfy oneself, and being online despite the destruction of one’s relationships, career, extra-curriculars and quality of life.

So how many people are struggling with it today? Though there is still no established diagnosis for the experience, researchers at the University of Hong Kong published a study in the journal Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking in 2014, estimating that 6 percent of the world is addicted to the internet which equates to over 400 million people.

But considering internet addiction has a high comorbidity and so rarely exists on its own, several individuals may simply be predisposed to abusing their tech. It can commonly coexist with depression, anxiety and ADHD. More research is required to understand how much is causing the other.

It’s difficult to state how many of us are exclusively addicted to the internet because of the internet itself and what “addicted” means considering the circumstances. But those of us consistently online do tend to experience mental health difficulties more so than those who aren’t.

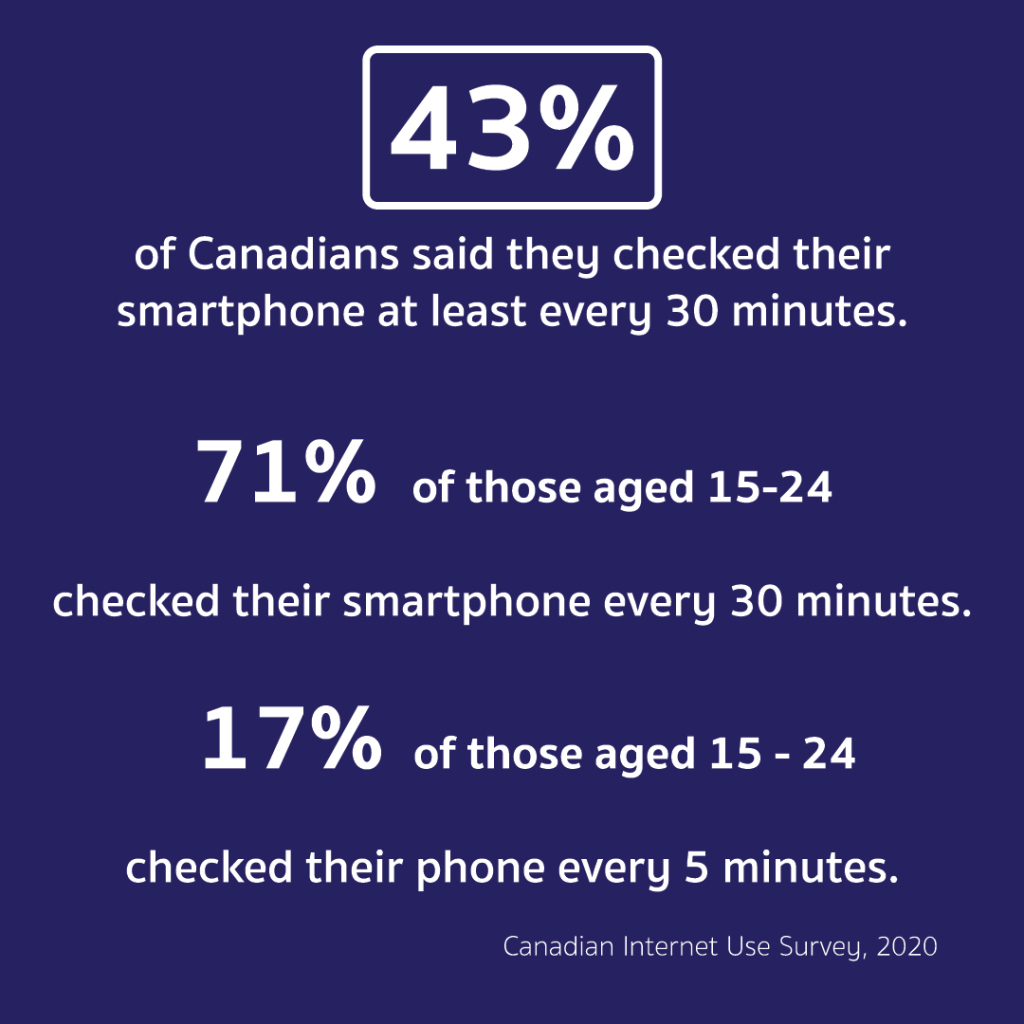

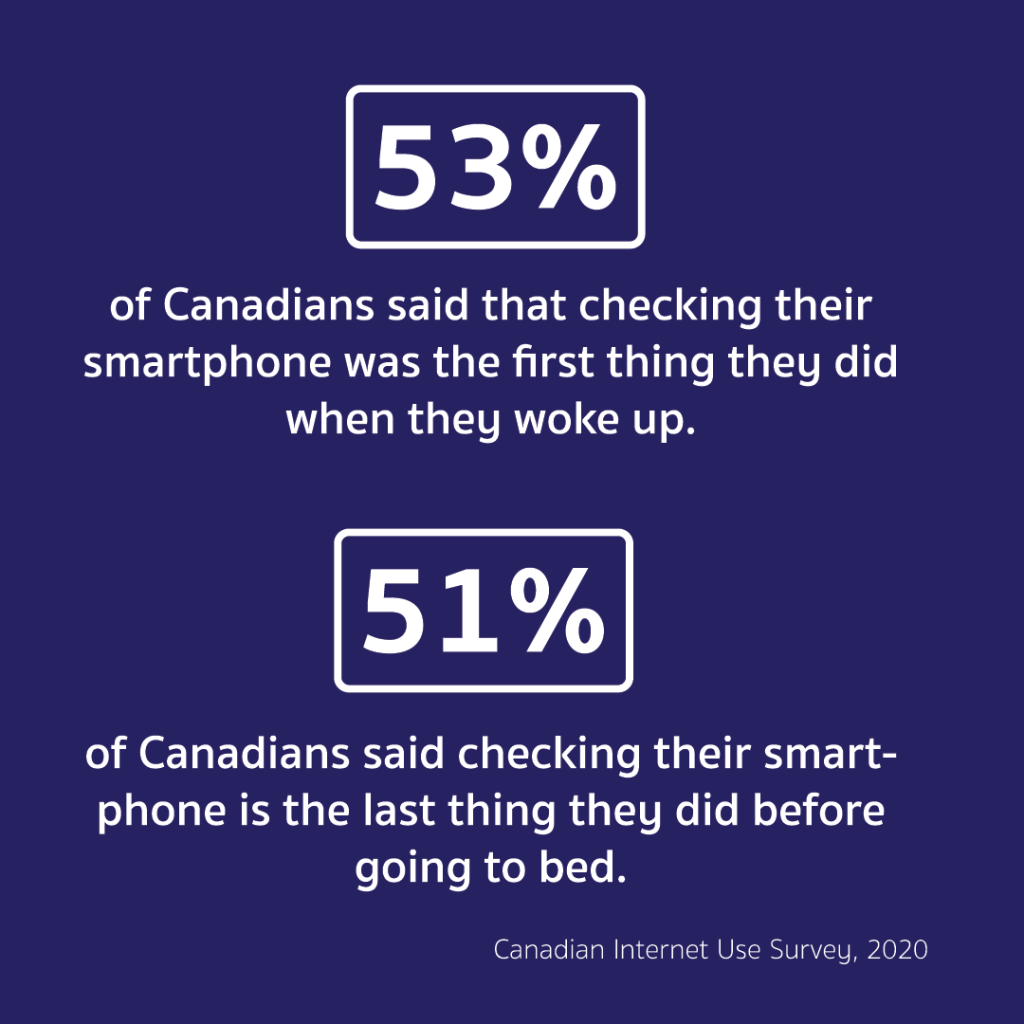

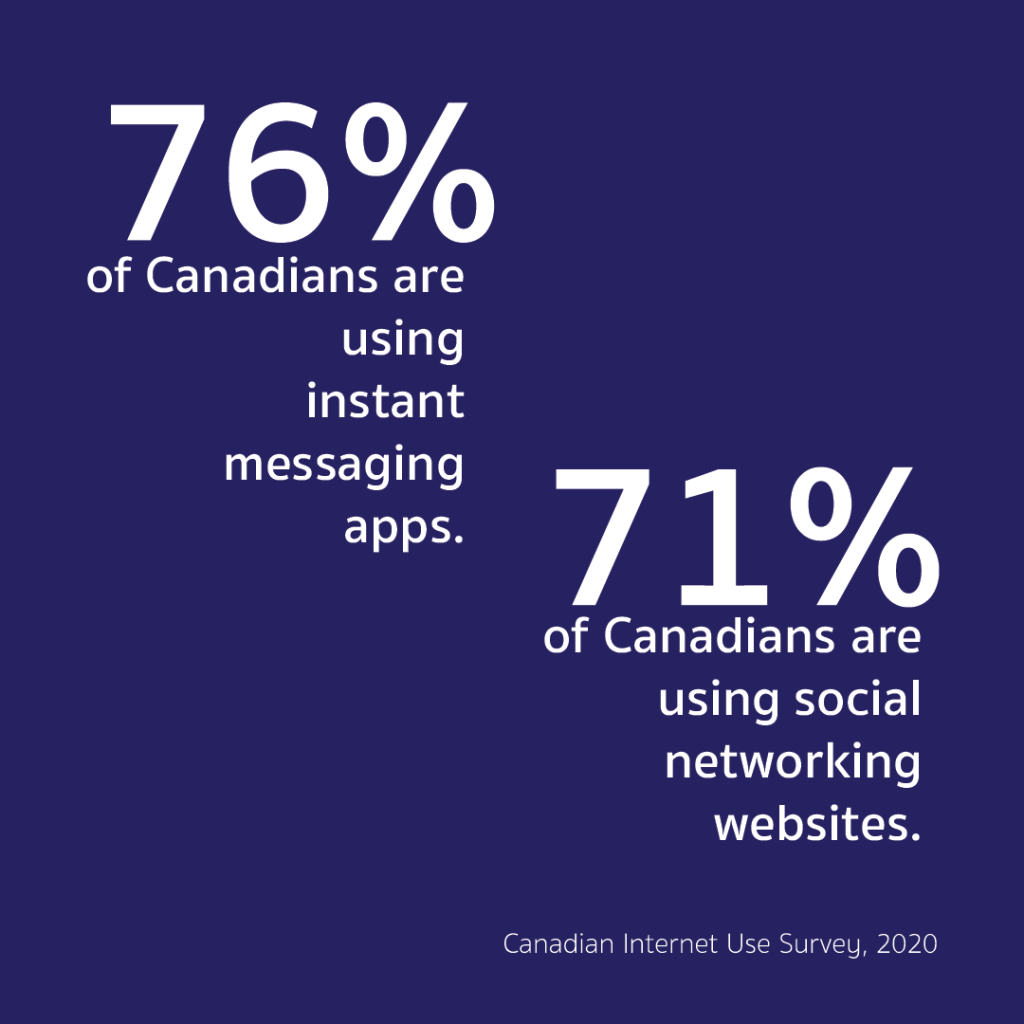

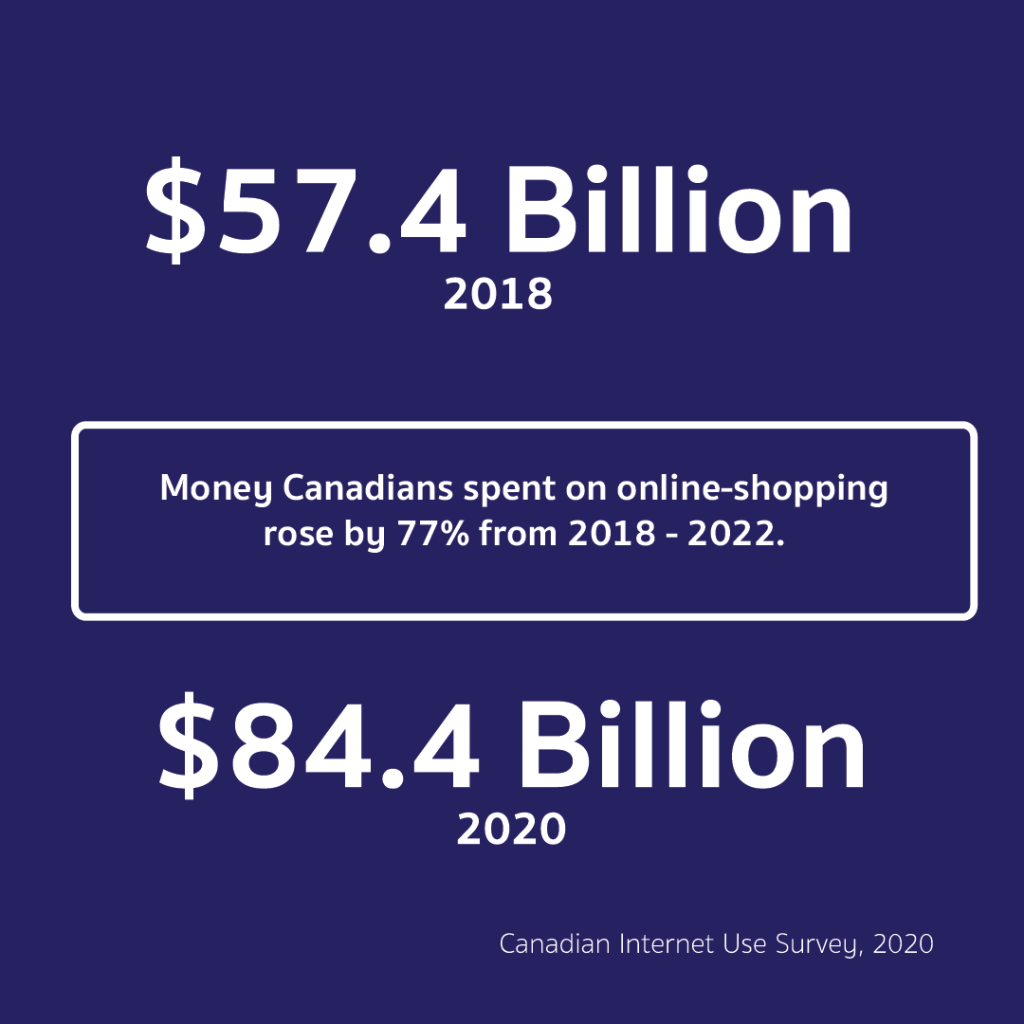

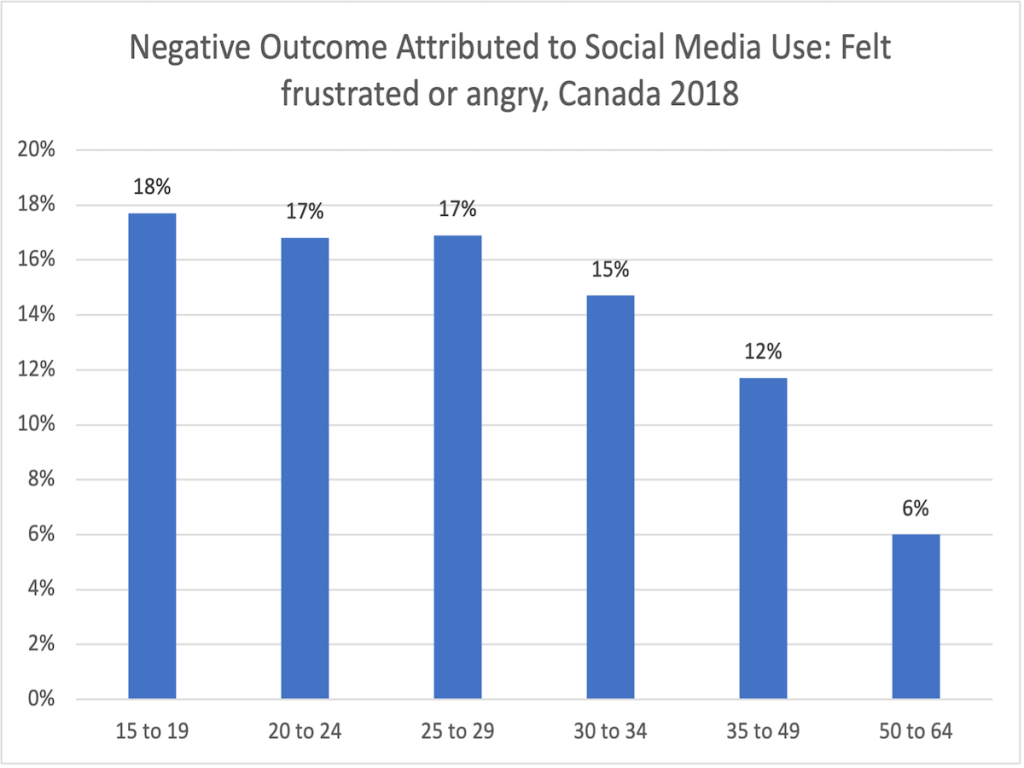

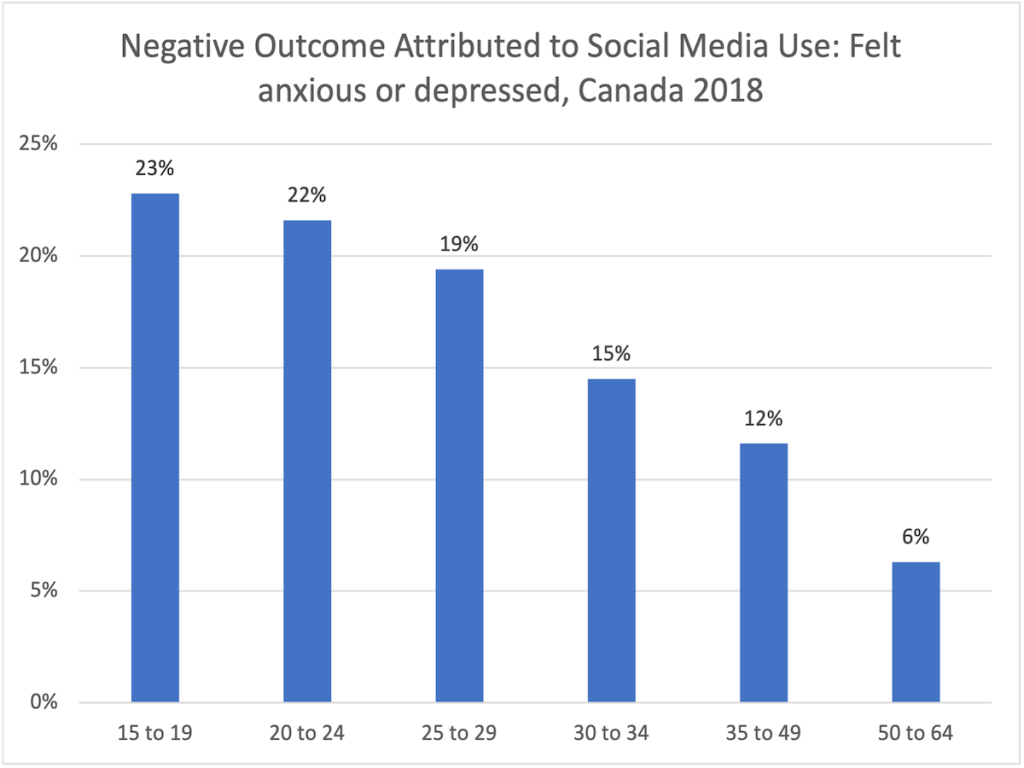

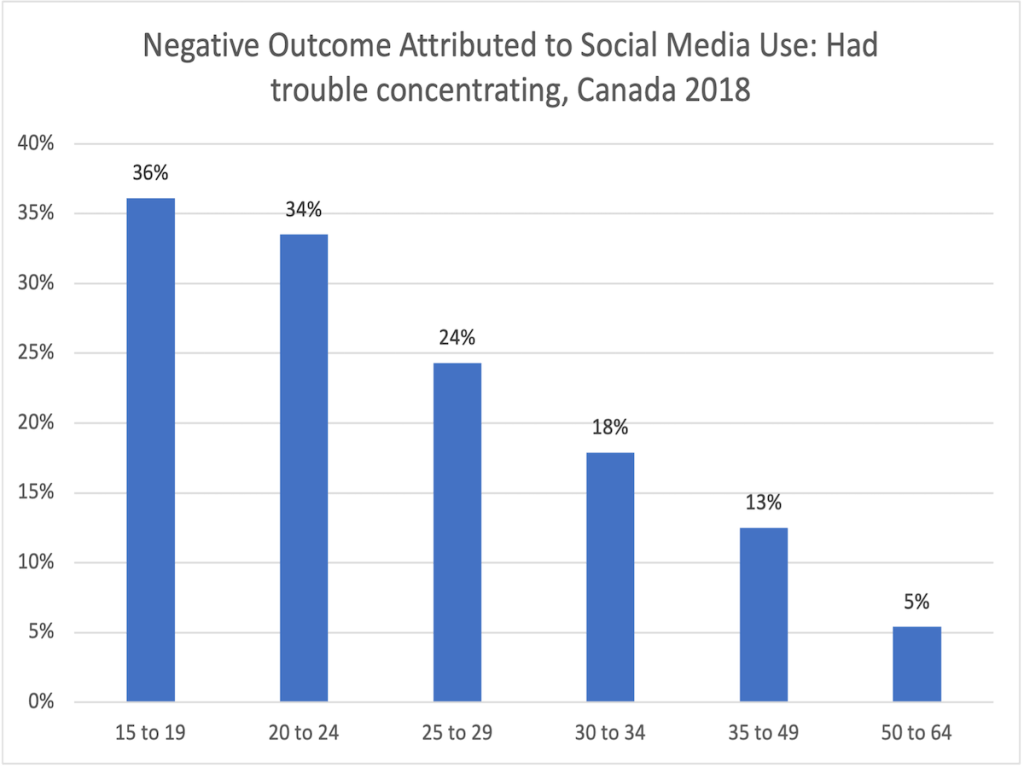

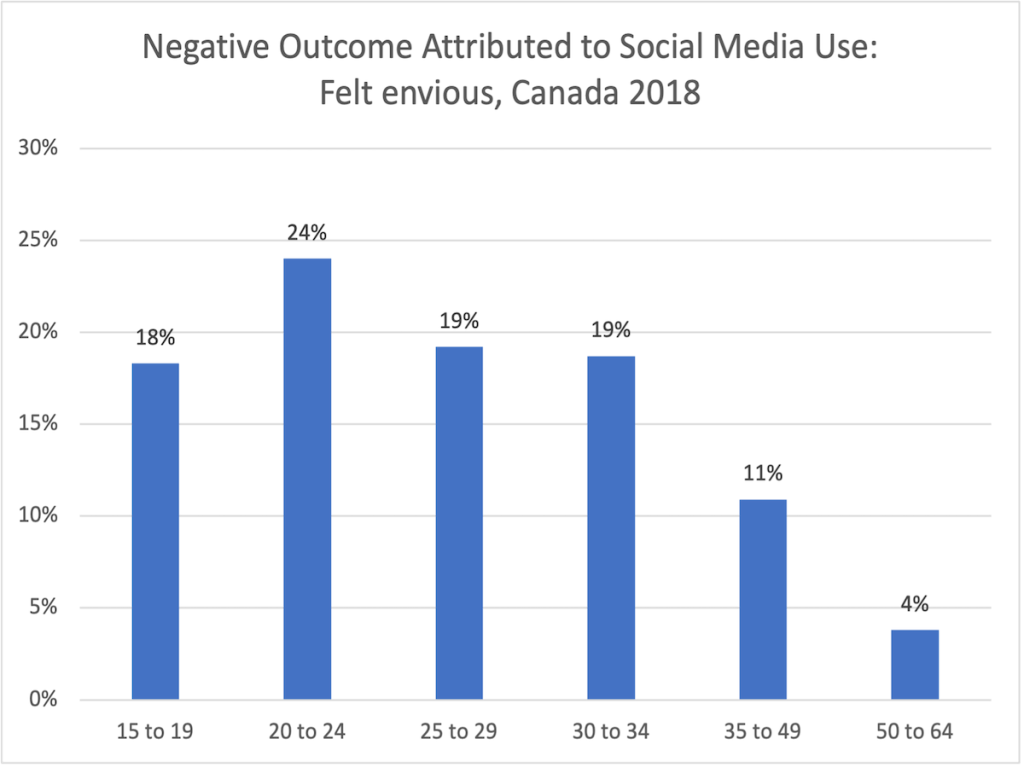

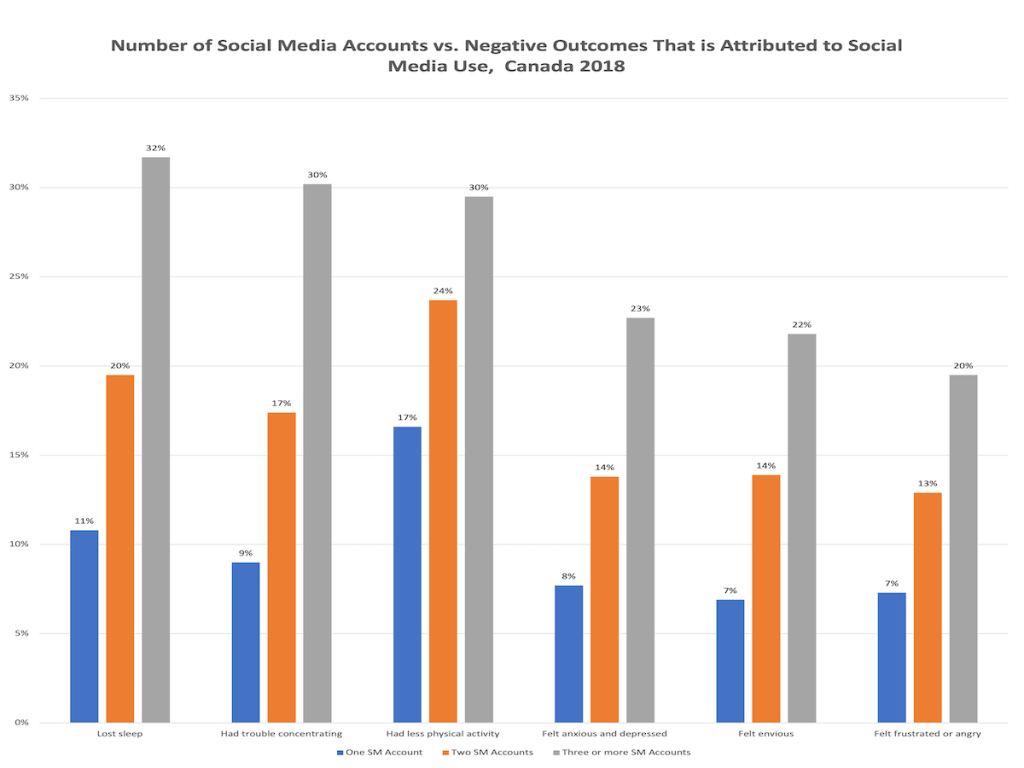

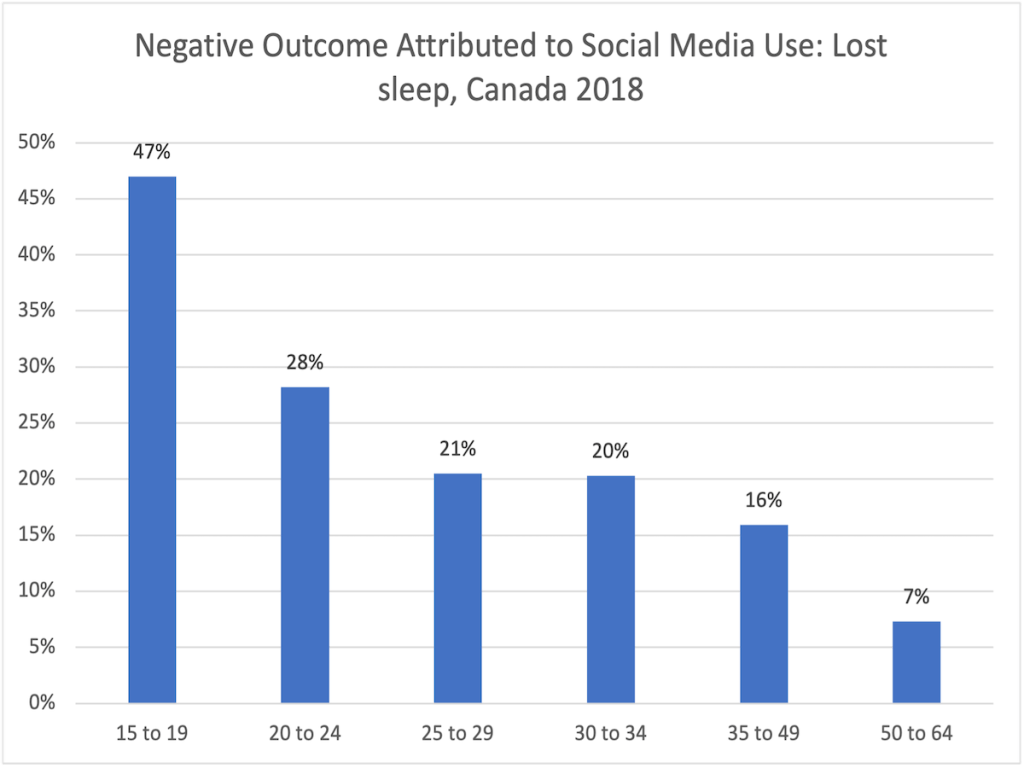

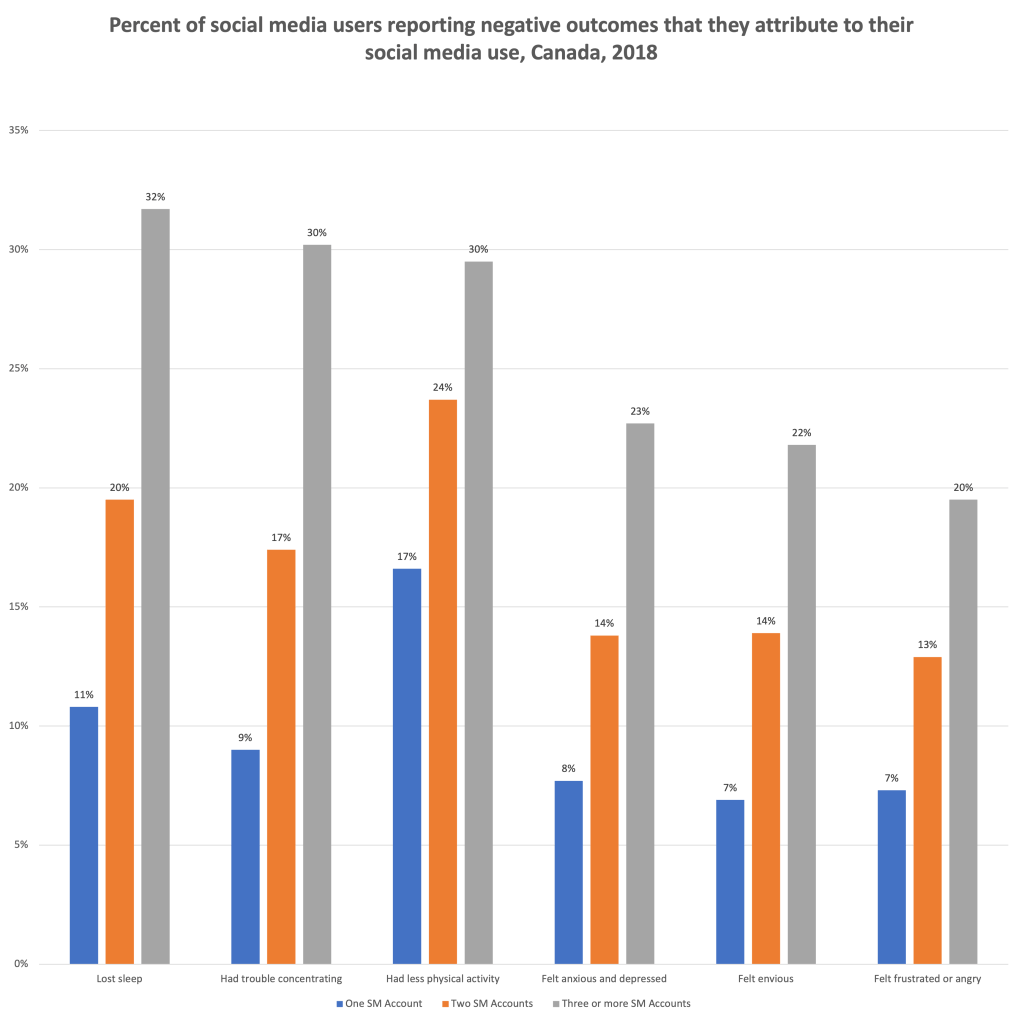

Social media for example, has been shown to have adverse effects when used in excess. The 2018 Canadian Internet Usage Survey details Canadians’ sentiments towards their social network use. Avid users reported higher rates of anxiety, depression, difficulty sleeping, lower physical movement, frustration, and feeling envious of other people’s lives than that of non-avid users.

Source: Statistics Canada, 2018 Canadian Internet Use Survey

Tech is harder, better, faster, stronger

Our relationship with technology is becoming less black and white and noticeably more enmeshed as it’s almost inescapable. Decisions can be (and are being) made for us through Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the ability for machines to know us so intimately can be seen as both a blessing and a curse.

AI is no longer an enigma and has added an entirely new dimension to internet applications and its relationship to addiction. A glaring example would be the invention of TikTok. The app used by a billion people monthly is owned by ByteDance. The company has also created the Chinese version of TikTok, Douyin. Both apps share similarities in their algorithm however do differ in some ways. The success of these tech sensations can be mainly credited to the recommendation algorithm. While years before, people had to search and unwearyingly wait for their content to load, now it’s instantaneous.

In a grossly simplified version, the algorithm is divided into two parts: first is the organization of content and second is the matching of the content to the user. The multitude of videos are organized into sections based off topic and are further specified and niched down. Then through a continuous process of assessing user interests, identity and behaviour data, the content is matched.

A repetition of physical movements is required to eventually recognize patterns (i.e., scrolling), but once the users’ patterns are learned the environment created becomes highly intoxicating – and the time lost when using the app is nefariously built by design.

The algorithm collects detailed information about the user, and this data is integral to optimizing the process. If you choose to login via an existing external account such as through Facebook or Google, the first increments of data will be collected via these profiles. If you make a brand-new account, your age and location information will be used by the algorithm to suggest your first batch of videos.

The Wall Street Journal investigated the TikTok algorithm and found that the recommendations start quite broad but can eventually match the user immaculately. The stream begins with the most popular content and provides a range of suggestions that can vary from religion to crocheting to erogenous behaviour. The conduct of the user will begin to dictate what video will be displayed thereafter. This includes all video interactions such as pausing, rewatching, commenting, liking, saving and so forth. The video’s emotional mood, sounds, captions and content will be captured as well. Data such as a user’s average watch time, duration of time spent on the app and log-on times are also collected.

To prevent monotony, the algorithm will display new subject areas that are recommended to profiles with similar interests and therefore may appeal to the user as well. The specification and unrelenting learning of the algorithm eventually keeps consumers in a wormhole of highly individualized content. Consumers receive a tailored list of videos that are seamless in length, topic, emotional mood, and boundless other factors that have been revealed through unique engagement patterns and is achieved through quite rudimentary means.

Guillaume Chaslot, a former Google engineer who worked on YouTube’s algorithms, said in the investigation, “the algorithm is able to find the piece of content you are vulnerable to, that will make you click, that will make you watch. It doesn’t mean that you really like it, or its content that you enjoy the most. It’s just the content that is most likely to make you stay on the platform.”

Big puddle, small jumps

Changes in human-technology interaction haven’t gone completely unnoticed. The EU data protection and privacy regulation, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), requires businesses to disclose how personal data is used. This includes how personal data is being applied in automated decision making as well as AI, however the full scope of AI’s capabilities aren’t covered in the regulation.

In 2021, the EU created their first proposal for an Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act that introduces increased government ruling within AI advancement and usage. The act consists of banning “high-risk” AI technology that can unconsciously manipulate someone into causing themselves or others harm. How this will be implemented or if it would even apply to potentially addictive algorithms, is yet to be discovered.

The Canadian data privacy law, Personal Information protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), is looking to receive an update to include AI technology and it’s subsequent encroachment on our personal data. And a bill in the US, introduced in 2019, called the Technology (SMART) Act appears to want to ban addictive features such as the infinite scroll and to even shut down apps after a certain period of activity.

Funnily enough, Aza Raskin, the inventor of the endless scroll, has rethought his development since he created it. Tweeting, “One of my lessons from infinite scroll: that optimizing something for ease-of-use does not mean best for the user or humanity.” He is now the co-founder of the Centre for Humane Technology, formed in 2018.

Some have taken their tech-obsessed matters into their own hands using self-help resources.

There’s a book titled, Reset Your Child’s Brain: A Four-Week Plan to End Meltdowns, Raise Grades, and Boost Social Skills by Reversing the Effects of Electronic Screen-Time by Victoria Dunckley with 600 reviews on Amazon and over 400 5-Star ratings. Not to mention all the fruity tech detox camps that have opened promoting natures unbelievable healing powers.

On the apps themselves, influencers are attempting to make a difference in consumers’ gratuitous behaviour. Social media creator @seanoulashin produces short videos that disrupt users’ senseless scrolling by promoting self-awareness. When the video displays on your feed, Oulashin guides you through a moment of mindfulness mid-scroll.

In one video he tells his viewers, “Hey you look like you’re on autopilot, like you’ve just been scrolling for way too long. Let’s fix that! We’ll start with your posture, how is it? Is your back up straight or do you look like you’re 80 years old? Next, we’ll go to your eyes. Do they still work? They’ve been fixed on the screen so try moving them left to right. Are they still there? How about your nose? Can they still do a good inhale?”

He conducts users through a couple of deep breaths and after the moment of intentionality, he tells them to continue scrolling with purpose.

Willpower vs. information whirlpool

Which brings into question, is internet addiction our job to change or Silicon Valley’s? Nir Eyal author of, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, believes it’s the users’ responsibility to control their tech use despite his desirable invention.

Eyal’s “Hooked” model explains how to build experiences that create patterns in consumers that will make them return to your product. This is achieved through the variable reward system.

When users are given an experience that oscillates from highly satisfying to mundane, the user is likely to return frequently with the prospect of receiving the positive disposition again. On a neurochemical level euphoric feelings such as serotonin and dopamine flood your brain depending on the type of stimulant received, and if these are desired chemicals you lack in your daily routine, you may be tempted to use technology as a quick fix without realizing. An example of this can be social media notifications that surprise you with a burst of encouraging engagement that boosts your dopamine levels which then persuades you to check back habitually only to see little to no engagement shortly after. The mixed bag experience elevates users’ incentive to stay hooked.

Regardless of this model and other addictive experiences, he believes that humans have the willpower to withstand such creations and so regulating or banning them should fall unnecessary.

In his article, The Addictive Product Myths: Who’s the Culprit Here, he highlights the complexities of addiction. Summarizing research in substance abuse, he notes that it’s not the substance itself that gets people hooked rather the distress that is remediated by the consistent use.

“It doesn’t matter how high the high or how enjoyable the experience might be. Addiction is not about how good something makes people feel, but rather what happens after the initial sensation fades. It’s not pleasure per se that drives us, but rather the desire to escape discomfort. No matter what it is, if a substance or behaviour helps us escape pain, someone is going to overuse and abuse it,” he writes about addictive behaviour.

Eyal emphasizes the risk of generalizing the term “addiction” and how it can border on fearmongering. As most of us aren’t addicted, just easily distracted. He also touches upon how this rhetoric can displace personal responsibility when it comes to one’s tech habits. He reinforces that believing you’re powerless against a situation absolves you of making changes.

Nonetheless, he does believe big tech should imbue some liability. He proposes a mediatory relationship between the business and consumer. Under what he calls the “Use and Abuse” policy, businesses that see individuals who are using their app or website excessively should be contacted and given resources to lessen their dependency. He notes that companies have extensive information of their consumers usage and have an ethical obligation to step in when problematic behaviour exposes itself. Through this avenue, addictive design elements that are appreciated by users with a healthy relationship to the internet can still enjoy the cyberspace as it is.

On the flip side, UX (User Experience) designers believe that they do have a part in creating less mind-altering digital experiences and are sharing techniques to make tech more favourable for everyone.

Utilizing AI, designers can integrate themselves further into the creation process and generate a healthy environment for consumers through algorithmic processes that detect signs of addictive patterns and varying the feed presented to the user to disrupt it. This way, knowledge of user-behaviour can be turned into a benefit for the participant as well. Designers can also use their algorithmic knowledge to add a feature for users to view the personal information applied to provide their current digital experience and therefore, deliver transparency.

Interface design that promotes a user’s awareness of their personal use is recommended to uphold autonomy. These can include adding check-ins or reminders at time intervals about usage, slowing down speed, and providing an option for a visual timer.

Tiptoe through the window

I consider having a kindship with the web. I admire it profusely and am wholeheartedly grateful to be born at a time of abundant knowledge, opportunity and frankly speaking – change.

Decades ago, people struggled with chatrooms, gaming, and inappropriate online content – and they still do. But now the internet is not only a one-size-fits-all adhoc pill for misery, but its new purpose is also to become an alluring, cozy, personalized space that invites you in and sits you down for tea while providing you with everything you need before you realize you even need it.

How do you tell someone to resist that? And if it is to be stopped, what would that even look like? Scholars such as Shoshana Zuboff, author of Surveillance Capitalism, strongly believes that the translation of human experience into data should be illegal, as it’s not only unethical – but takes away human autonomy. However personal data and its nefarious uses is a rabbit hole I will discuss in another article, but I thought it was important to mention that the ethics of addictive technology (and it’s driving forces: our data) is under scrutinization.

And while I don’t think tech companies are completely innocent, I don’t think we are silent victims either.

You can be mindful of your tech use, set intentions before picking up a device and most importantly – figure out the reason you are trying to so ardently escape. On the contrary, while self-accountability is indispensable, with the anthropological structure of our brains and thumbs transforming, I do think it’s necessary to keep a close eye on how technology continues to impact us and adjust as we go.

If you are concerned with your internet usage, please seek counselling and talk to someone you trust. Sending you love and support.

Leave a comment